Reptilian digestive tract specializations are remarkably adapted to their diets. Herbivorous reptiles have evolved longer small intestines for better nutrient absorption and larger body sizes to support greater gut capacity. Their digestive systems often feature ceca for microbial fermentation and colonic valves that slow food passage, allowing for effective fermentation. They also have symbiotic relationships with gut flora, particularly hindgut nematodes, which help break down plant fibers. In fact, over 95% of herbivorous liolaemid lizards benefit from these nematodes. These complex adaptations ensure efficient processing of their fibrous diets. There's more to explore about these fascinating digestive strategies.

Key Takeaways

Herbivorous reptiles have evolved longer small intestines to maximize nutrient absorption from their plant-based diets. In some reptiles, specialized features like ceca and colonic valves slow down food passage, allowing for better fermentation. The gut flora of herbivorous reptiles, including hindgut nematodes, plays a crucial role in enhancing digestive efficiency. Larger body size also allows for greater gut capacity, enabling these reptiles to extract more nutrients from their diets. The symbiotic relationship between reptiles and nematodes helps break down fibrous plant materials, making it possible for them to thrive on plant-based diets.

Herbivorous Adaptations

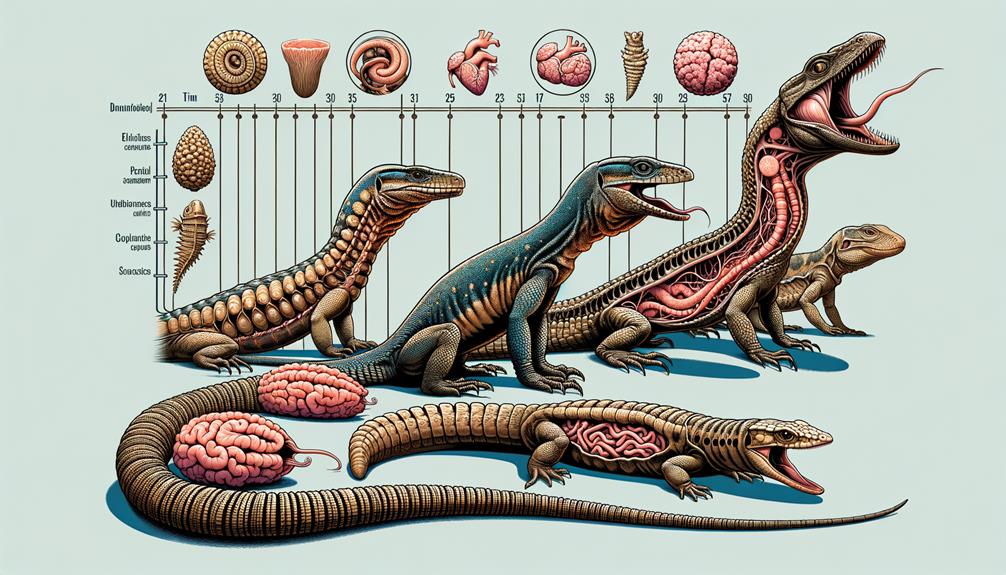

Herbivorous liolaemids have distinct physical features that allow them to efficiently process plant matter. These adaptations are crucial for their diet, enabling them to extract nutrients from fibrous plant material. The digestive tract of these reptiles is relatively complex, despite lacking the specialized features seen in other herbivorous reptiles. Instead, they have a longer small intestine, which is vital for maximizing nutrient absorption.

The larger body size of herbivorous liolaemids supports a greater gut capacity, further enhancing their ability to digest and assimilate nutrients from plant matter. Many of these herbivorous species also have hindgut nematodes, which likely help break down complex plant fibers, facilitating plant matter digestion and nutrient extraction.

The relationship between diet and body size in these reptiles highlights the importance of physical adaptations in their digestive efficiency. These findings challenge the conventional view that intricate gut specializations are necessary for herbivory in reptiles. Instead, they show how basic physical adaptations, such as increased intestine length and larger gut capacity, can be sufficient for a mainly plant-based diet. This insight provides a clearer understanding of the essential adaptations required for herbivory.

Gut Morphology

<|start_header_id|><|start_header_id|> the gut morphology of these lizards. in the text

Ceca and Colonic Valves

In exploring the role of ceca and colonic valves in herbivorous reptiles, I've found that these structures significantly boost digestive efficiency. By allowing for prolonged fermentation, they maximize nutrient extraction from plant material. This adaptation is crucial for reptiles to thrive on plant-based diets, and understanding it sheds light on the diverse strategies they employ to survive.

Function and Importance

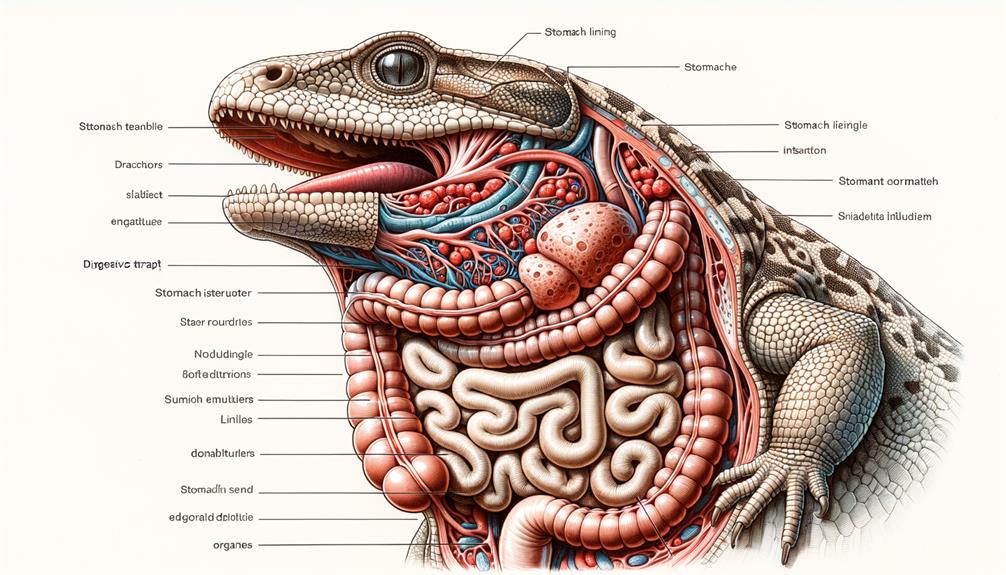

To understand how efficiently reptiles digest their food, let's take a closer look at the cecum and colonic valves. These specialized parts of the digestive tract are crucial for herbivorous reptiles, as they help break down and extract nutrients from plant-based foods.

The cecum is a site of microbial fermentation, where microbes break down cellulose and complex carbohydrates into nutrients that can be absorbed by the body. This process is vital for larger reptiles, as they need to extract as many nutrients as possible from their plant-based diet.

Colonic valves slow down the passage of food through the gut, allowing for more time to ferment and absorb nutrients. This is especially important for reptiles that eat a lot of plant matter, as it gives them a chance to extract as many nutrients as possible.

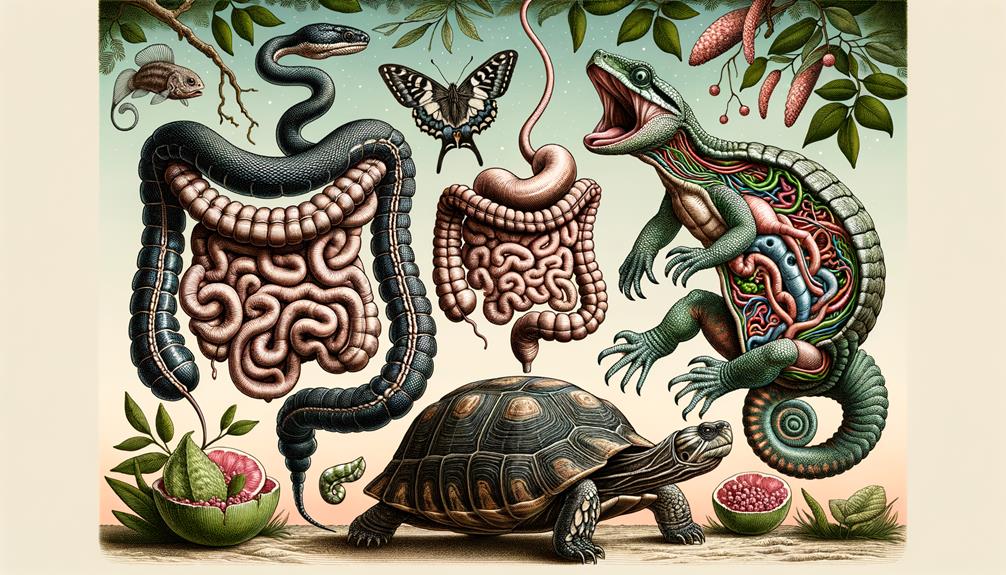

While many reptiles, like iguanas and tortoises, have these specialized digestive features, others, like some species of lizards, do not. Instead, they have evolved other adaptations, such as longer small intestines, to help them digest their food.

The presence of these specialized digestive features is closely linked to the type of food reptiles eat. By understanding how these features work, we can gain a better appreciation for the amazing diversity of digestive strategies found in reptiles.

Evolutionary Adaptations

While exploring the function and importance of ceca and colonic valves highlights their role in nutrient extraction, examining evolutionary adaptations reveals how some herbivorous reptiles thrive without these specialized gut features. Herbivorous liolaemids, for example, lack ceca and colonic valves but still manage to subsist on plant-based diets. This absence suggests they've developed alternative physical adaptations.

By comparing herbivorous liolaemids among dietary categories, we see that their simpler gut structure doesn't necessarily require greater gut complexity to process plant material. Instead, they exhibit a significant positive correlation between herbivory and the evolution of larger body size. This larger body size likely compensates for their lack of specialized gut features.

| Feature | Herbivorous Liolaemids | Specialized Gut Reptiles |

|---|---|---|

| Ceca Presence | Absent | Present |

| Colonic Valves | Absent | Present |

| Body Size | Larger | Variable |

Herbivorous liolaemids examined show that large intestine length and small intestine length are adapted differently compared to reptiles with complex guts. Their evolution of a larger body provides a model for understanding how reptiles can adapt to herbivory without requiring gut specializations. This suggests that herbivory favors the evolution of larger body size, which might be an alternative evolutionary pathway for nutrient extraction.

Symbiotic Relationships

In exploring symbiotic relationships, I've found that the gut flora of herbivorous liolaemid lizards plays a significant role in boosting their digestive efficiency. Specifically, these lizards harbor nematodes in their hindgut, which facilitates the breakdown and absorption of plant material. This mutually beneficial relationship compensates for the lizards' lack of advanced gut specializations, enabling them to effectively extract nutrients from their plant-based diet.

Microbial Gut Flora

Herbivorous liolaemid lizards have developed a unique relationship with nematodes in their hindgut, which is crucial for breaking down plant matter. These reptiles can't efficiently digest plants on their own, so they rely on the nematodes to help with the process. This partnership highlights the significance of gut microbes in enhancing digestion and nutrient absorption.

The presence of hindgut nematodes in herbivorous liolaemids is notable for several reasons. For instance, over 95% of these lizard species have nematodes in their hindgut, a much higher rate than their omnivorous and insectivorous counterparts. This is likely due to the strong link between herbivory and the presence of these gut microbes, with herbivores having twice the rate of omnivores and four times the rate of insectivores.

Despite lacking complex gut structures, these lizards thrive on plant-based diets, relying on the nematodes for effective digestion. This challenges the idea that complex gut morphology is necessary for herbivory in reptiles. Instead, it shows how microbial adaptations can complement or replace gut complexity. Understanding these interactions provides valuable insights into the evolutionary innovations and dietary flexibility of reptiles, allowing them to overcome their own digestive limitations.

In essence, this symbiotic relationship demonstrates that herbivorous liolaemid lizards have found a way to adapt and thrive on plant-based diets, thanks to the help of their gut microbes.

Digestive Efficiency Boost

The unique partnership between liolaemid lizards and hindgut nematodes significantly boosts the reptiles' digestive efficiency. Herbivorous liolaemids, in particular, have a much higher rate of hindgut nematodes compared to their omnivorous and insectivorous counterparts. This partnership is crucial for breaking down plant matter, allowing these lizards to extract more nutrients from their fibrous diets.

It's striking to see the high prevalence of hindgut nematodes in herbivorous liolaemids. Over 95% of them have these nematodes in their hindgut, which is the primary site for fermenting plant-based diets in reptiles. The presence of these symbionts facilitates the breakdown of complex plant fibers, leading to improved digestive efficiency.

| Type of Liolaemid | Prevalence of Hindgut Nematodes |

|---|---|

| Herbivorous | Twice as high as omnivores |

| Herbivorous | Four times higher than insectivores |

| Omnivorous | Lower than herbivorous |

| Insectivorous | The lowest among the three |

| Herbivorous with nematodes | Over 95% in hindgut |

This partnership between herbivory and hindgut nematodes in liolaemid lizards challenges the idea that sophisticated gut structure and function are solely responsible for efficient plant matter digestion. The presence of hindgut nematodes plays a vital role in enhancing the digestive efficiency of herbivorous liolaemids, highlighting a fascinating aspect of reptilian digestive tract specializations.

Dietary Strategies

Liolaemid lizards have evolved unique dietary strategies that allow them to efficiently process plant matter. As herbivores, they've developed distinct adaptations in their digestive tract that set them apart from their omnivorous and insectivorous relatives.

One notable adaptation is their larger body size, which enables them to have a greater gut capacity. This is essential for a plant-based diet, and the scaling pattern suggests a direct link between body size and digestive efficiency for herbivory.

Their gut morphology is also remarkable, particularly the longer small intestines. This compensates for the absence of a cecum and colonic valves typically found in other herbivorous reptiles, allowing them to effectively process fibrous plant materials.

Moreover, many herbivorous liolaemids have formed symbiotic relationships with hindgut nematodes. Over 95% of these lizards have nematodes exclusively in the hindgut, indicating that these nematodes play a crucial role in breaking down plant matter.

Their dietary strategies can be summarized as follows:

- Body Size: A larger body allows for greater gut capacity, essential for a plant-based diet.

- Gut Specializations: Longer small intestines compensate for the lack of a cecum, enabling efficient plant matter processing.

- Symbiosis: Hindgut nematodes aid in plant digestion, highlighting the importance of this symbiotic relationship.

Evolutionary Solutions

Through a unique combination of physical traits and partnerships with other organisms, liolaemid lizards have evolved clever ways to survive on a plant-based diet. These lizards have developed longer small intestines compared to their omnivorous and insect-eating counterparts. This extra length allows them to digest plant material more efficiently, making up for their lack of specialized gut features.

As herbivorous liolaemids grow in size, their gut capacity also increases, which helps them extract more nutrients from plants. This physical adaptation enables them to process large amounts of fibrous plant material, essential for meeting their energy needs.

Hindgut nematodes, found in over 95% of these herbivorous liolaemids, likely play a key role in their digestion. These nematodes, which live exclusively in the hindgut, may help break down plant matter, providing a symbiotic advantage that complements the lizards' digestive strategies.

The fact that these lizards can thrive without complex gut specializations challenges the idea that such features are necessary for reptiles to eat plants. Instead, liolaemid lizards offer a simpler model for understanding how basic physical adaptations and partnerships can enable herbivory, showcasing their unique approach to surviving on a plant-based diet.

Frequently Asked Questions

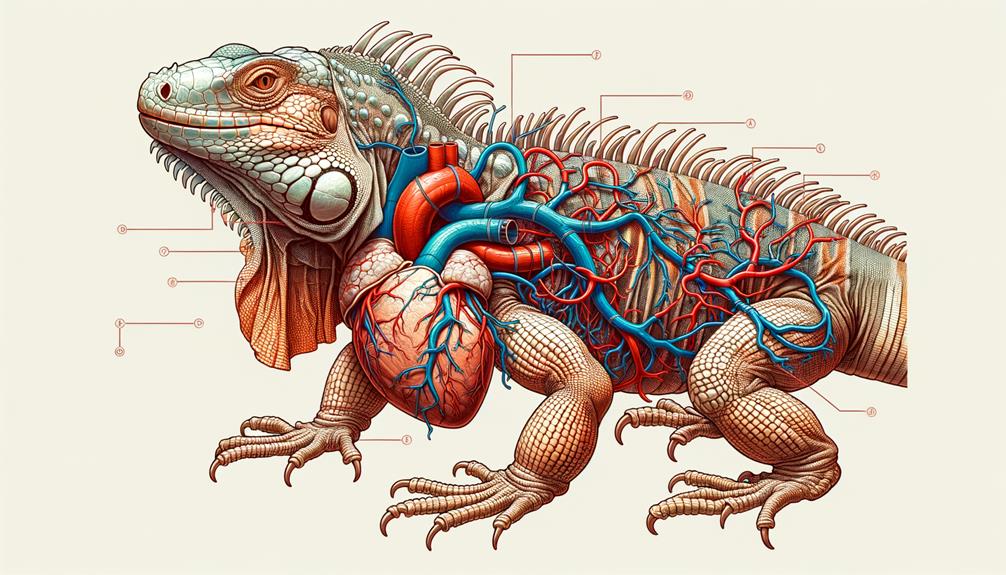

What Type of Digestive System Do Reptiles Have?

Reptiles have a complex digestive system that includes the mouth, salivary glands, esophagus, stomach, intestine, and cloaca. This system efficiently processes food and waste, allowing them to thrive in both aquatic and terrestrial environments while conserving water.

What Is the Difference Between the Alimentary Canal of Reptiles and Mammals?

When I examined a python's digestive system, I noticed its intestines were shorter and less specialized compared to those of mammals like rats, reflecting their distinct dietary needs. Mammals have more complex alimentary canals, accommodating diverse and specific functions.

What Are the Different Types of Digestive Tracts in Animals?

Animals have developed different types of digestive tracts to adapt to their specific diets. There are monogastric, ruminant, and hindgut fermenters, each with unique complexities and efficiencies that allow for optimal nutrient extraction. I've had the opportunity to study these systems, and I appreciate how they've evolved to meet the needs of their respective species.

What Is the Digestive System of Reptiles Explain?

Imagine navigating a complex path: that's the reptilian digestive system. From the mouth to the esophagus, then the stomach, intestines, and finally the cloaca. Each stage plays a vital role in their ability to absorb nutrients efficiently.