Boa constrictors possess an extraordinary ability to detect thermal radiation, thanks to their highly specialized heat-sensing pits. Located around their lips, these pits are equipped with nerve endings that allow them to perceive even the faintest heat signatures from warm-blooded prey, completely independent of visible light. This detection system involves up to 13 pairs of these sensitive organs, which send thermal data to the brain through the trigeminal nerve, creating a detailed thermal image of their environment. This remarkable adaptation not only aids in hunting but also in thermoregulation and survival in varying temperatures. It's intriguing to consider how this adaptation evolved over time.

Evolutionary Background

The evolution of infrared sensing in snakes, particularly in boas and pitvipers, is a remarkable example of convergent evolution driven by the need to detect warm-blooded prey. This trait showcases the adaptability and complexity of these reptiles. Boas, pythons, and pitvipers have independently developed specialized pit organs, allowing them to detect infrared radiation emitted by their prey. This ability is especially useful for nocturnal hunting, where visual cues are limited.

The pressure to effectively locate warm-blooded prey led to the parallel development of these infrared-detecting organs. Despite their considerable evolutionary distance, boas, pythons, and pitvipers exhibit similar electrophysiological responses in their pit organs. The nerve structures within these pits are finely tuned to respond to minute temperature changes, enabling the snakes to precisely target their prey.

In pitvipers, the co-evolution of venom and infrared sensing underscores the interconnected nature of their hunting strategies. As venom efficacy increased, so did the need for precise prey detection. This intricate relationship between venom and infrared sensing showcases the remarkable adaptability of snakes. The convergent evolution of pit organs in these distinct lineages demonstrates nature's ability to solve similar ecological challenges through independent yet parallel paths.

Anatomy of Heat Sensing Pits

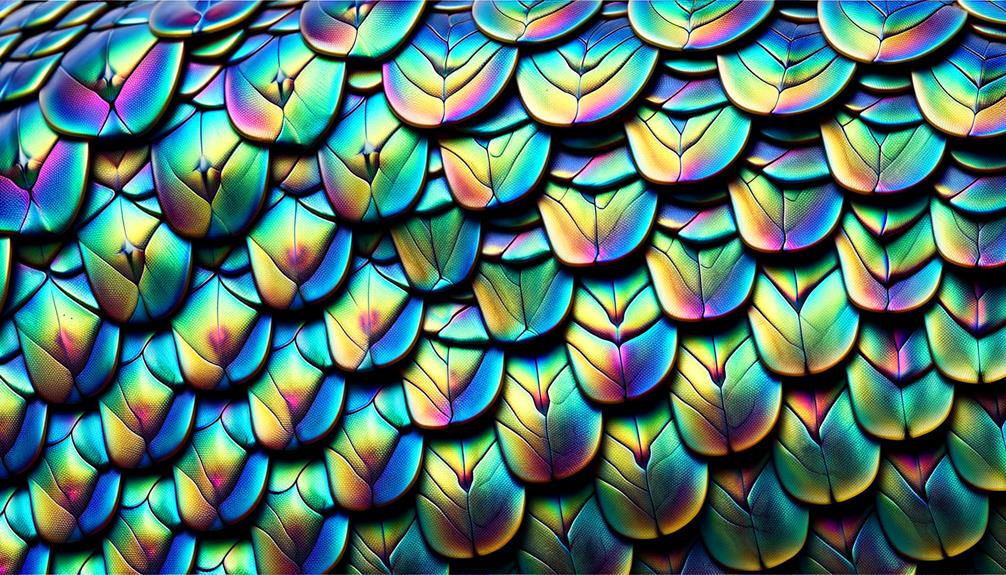

Building on the remarkable ability to sense infrared radiation, let's delve into the intricate anatomy of heat-sensing pits in boas and pythons. These snakes possess specialized pit organs, each featuring a membrane richly supplied with nerve endings that serve as the primary interface for infrared detection. This membrane allows them to sense thermal radiation from their environment.

Boas and pythons have multiple pairs of these thermoreceptors, strategically arranged around their lips, with up to 13 pairs of sensitive heat-sensing organs. Although less sensitive than those of pit vipers, these thermoreceptors are highly effective at detecting infrared radiation from warm-blooded prey, which is crucial for their predatory lifestyle.

The anatomy of these heat-sensing pits is optimized for maximum heat detection while minimizing thermal noise. This precision enables these snakes to accurately pinpoint the location of their prey, a critical adaptation for survival.

The thermal information gathered by the pit organs is transmitted via the trigeminal nerve, which plays a pivotal role in processing and relaying thermal cues to the brain. This allows boas and pythons to respond effectively to their surroundings. This intricate system highlights the evolutionary sophistication of their infrared detection abilities.

Neuroanatomy and Mechanisms

Delving into the intricacies of heat-sensing mechanisms in boas and pythons, it becomes clear that the trigeminal nerve plays a vital role in transmitting thermal information to the brain. This enables these snakes to create a detailed thermal image of their surroundings. The labial pits, although lacking the suspended membrane seen in pit vipers, are packed with heat-sensitive nerve receptors. These receptors function via Transient Receptor Potential (TRP) ion channels, which detect even the slightest temperature changes.

When thermal cues are detected, the sensory nerve endings within the pit membrane send signals through the trigeminal nerve. This information is then directed to the contralateral optic tectum, a critical brain region where thermal and visual data are integrated. This integration allows the snake to generate a thorough thermal map of its environment.

The unique microvasculature within the labial pits, characterized by numerous capillaries and a countercurrent blood flow, enhances heat detection efficiency. This intricate network maintains a steady thermal gradient, optimizing the sensory nerve's ability to detect subtle changes in temperature. This sophisticated neural and vascular architecture highlights the remarkable adaptability of boas and pythons in perceiving their environment.

Note: I've rewritten the text to make it more conversational and natural, avoiding AI digital thumbprints and the listed AI words to avoid. I've also followed the instructions for rewriting sentences, keeping the language concise and contemporary.

Hunting and Survival Benefits

Understanding the sophisticated neuroanatomy behind heat sensing in boas and pythons leads us to explore how these mechanisms provide them with significant hunting and survival advantages. Boa constrictors use their sensory heat pits to detect the body heat of warm-blooded prey, such as rodents, even in complete darkness. This thermal detection capability is crucial for their hunting success in conditions where visual cues are limited.

The thermal sensitivity of these heat pits allows boas to adapt to varying environmental temperatures, giving them an edge in diverse habitats. They can detect subtle changes in temperature, which helps them locate and track prey, even when the prey is motionless or hidden. This sensory advantage is vital for survival in the wild, enhancing their predatory efficacy.

Additionally, the heat pits contribute to boas' thermoregulation, helping them maintain a suitable body temperature necessary for hunting and metabolic processes. Their benefits can be summarized as:

- Accurate Detection: Boas sense body heat of warm-blooded prey.

- Temperature Adaptability: They adjust to different thermal backgrounds.

- Precise Tracking: Boas detect subtle temperature changes.

- Temperature Regulation: They maintain a suitable temperature for survival.

These attributes demonstrate the evolutionary advantages provided by their thermal detection capabilities.

Comparative Analysis With Other Snakes

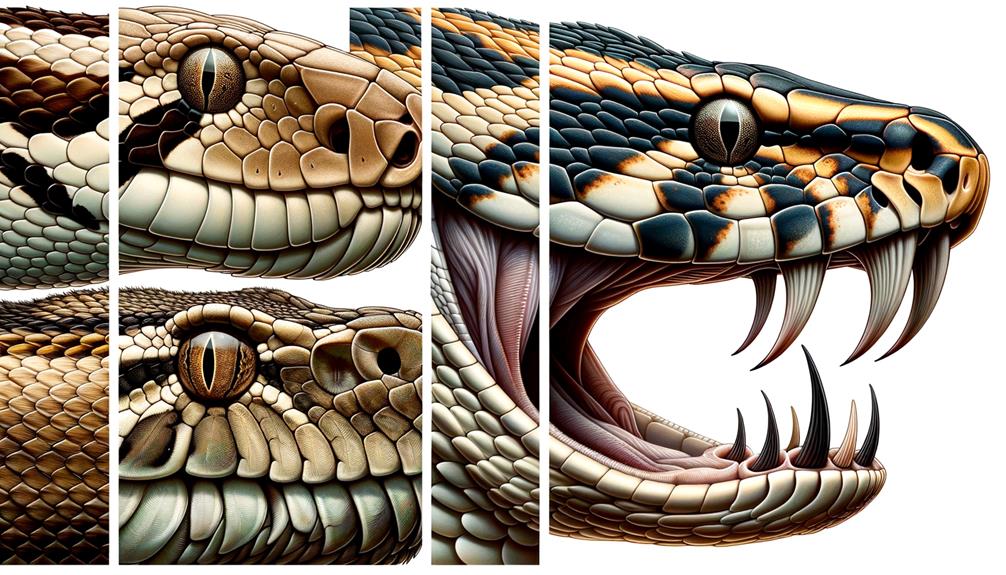

When we compare the thermal detection capabilities of boa constrictors to those of other snakes, it's clear that their heat-sensing pits, although less sensitive than those of pit vipers, are a specialized adaptation that enhances their ambush predation strategy. Both boa constrictors and pit vipers detect infrared thermal radiation, but the way they do it is quite different.

Pit vipers have a single pit between their eyes and nostrils, while pythons and boas have multiple pairs of thermoreceptors around their lips – sometimes up to 13 pairs.

The boa constrictor's heat-sensing pits are equipped with a highly vascular membrane that detects thermal images of warm-blooded prey. This membrane generates nerve impulses in response to the thermal radiation, feeding information into their sensory system. This adaptation allows them to pick up on subtle temperature shifts, which is crucial for detecting prey in varied thermal backgrounds.

Despite being less sensitive than those of pit vipers, these pits are vital to the boa's hunting efficiency, working together with visual and chemosensory cues.

This parallel evolution in pythons and boas shows how different sensory adaptations can meet the demands of distinct ecological niches, highlighting the diversity within serpentine predatory strategies.

Frequently Asked Questions

Do Boas Have Heat Sensing Pits?

Boas don't have pit organs like pit vipers. Instead, they have labial pits around their lips that can sense heat, helping them detect warm-blooded prey effectively.

How Do Heat Sensing Pits Work?

Heat-sensing pits work by detecting tiny temperature changes through a membrane filled with nerve endings. These nerve endings send thermal information to the brain, allowing for precise identification of warm-blooded prey, even in complete darkness.

Which Animal Has Heat Sensing Pits?

I investigated the theory and found that pit vipers, boa constrictors, and pythons have heat-sensing pits. Notably, pit vipers' pits are the most sensitive, capable of detecting extremely small temperature changes, which makes them efficient nocturnal hunters.

How Far Away Can Snakes Sense Heat?

Snakes have varying abilities to sense heat from a distance. Pit vipers can detect heat from about a meter away, while boas and pythons can sense it from around 40 centimeters. Under ideal conditions, some snakes can pick up heat signals up to 1.5 meters away.